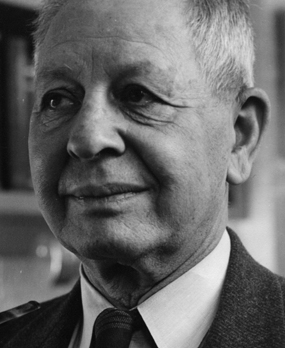

Elvin C. Stakman (1885-1979):

How he has transformed the scene

A $15 Investment Pays World-Wide Dividends

Fifteen dollars. That's what Elvin Stakman paid for his first semester at the University of Minnesota in the fall of 1902. It must have been hard to imagine then that this $15 would be the first step in an academic career that spanned 70 years and changed the face of modern agriculture.

The youngest of four children, Stakman was born on a farm near Ahnapee, Wisc. His family moved to Brownton, Minn., while he was an infant, and he loved this little town located about 75 miles west of Minneapolis. He spent his first post-college years as a high school teacher in Red Wing, Minn., Mankato, Minn., and as a teacher and superintendent of the high school in Argyle, Minn. In 1909 he was offered a position in the University of Minnesota's Department of Vegetable Pathology (which today is known as Plant Pathology).

He remained an active member of this department — serving as department head from 1940-1953 and even celebrating his 93rd birthday with Plant Pathology graduate students — for the remainder of his life.

From One Small Farm to A Whole New World of Farming

Stakman received his M.A. in 1910, and his Ph.D. in 1913. While researching "bridging hosts" in black stem wheat fungus for his Ph.D., Stakman revolutionized understanding of this destructive plant disease, which was threatening the world's wheat supplies, and was a serious concern for the global food supply. His work eventually reduced black stem fungus from a devastating crop plague to a minor problem. Consider, for example, that between 1917 and 1935, black stem rust destroyed more than 20% of U.S. wheat crops several times. The last U.S. outbreak was in 1962, with 5% of the crops destroyed.

Stakman believed that science — in particular, agricultural research and application — could be a powerful force for improving the lives of people around the world. He saw a growing need for an increased food supply to provide nutrition, health and general well-being of an ever-growing world population.

So it's no surprise that Stakman's work in the 1940s sowed the seeds of what was to become known as the "Green Revolution" in agriculture — the large-scale implementation of a variety of agricultural research and technology advances that increased food production around the world, particularly for developing countries. With funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, he helped establish a network of centers for agricultural and economic improvement in developing countries, starting with Mexico in the 1940s and expanding to Chile, Columbia, the Philippines, and India. By the mid-twentieth century, the "Green Revolution" was credited for saving more than one billion people from starvation. One of Stakman's students, Norman Borlaug, became known as the "Father of the Green Revolution" and received the 1970 Nobel Peace Prize.

Contributions Long Remembered

Stakman died on January 22, 1979, just four months before his 94th birthday. His wife passed away in 1962, and they had no children. He left the bulk of his estate to the University of Minnesota's Department of Plant Pathology to further research in the field he loved. He received countless awards throughout this life, and in the 1950s was named one of the 100 most important men in the world. He published more than 300 papers, several books, and held regular or honorary memberships and degrees from distinguished associations and universities across the globe. Stakman Hall was named for him on the University of Minnesota's St. Paul campus, and today is home to the department of Plant Pathology.